The change wasn’t loud. It came in the form of new locks.

One morning, Musah arrived at the supply room to find his key no longer fit. The metal teeth, once familiar, now met resistance. He tried again. Nothing. The door remained shut.

Across the compound, similar stories unfolded. The office doors, the linen store, the generator shed—each had been fitted with new locks. The keys had changed. And so had the hands that held them.

Hospitality Associates had begun their operational rollout. New staff were recruited—front office, housekeeping and food service personnel—with unexpected interference from community leaders and chiefs once word of the recruitment spread. Recommendations poured in, some helpful, others politically charged. The lodge, once run by a tight-knit group of rangers, now felt like a stage for competing interests.

Their uniforms were crisp. Their names unfamiliar. The rangers, once the heartbeat of Savannah Lodge’s daily rhythm, now hovered at the edges.

Kojo, the senior receptionist, had been retained. But he no longer moved with the same ease. His role had changed, and so had the way others saw him.

The swimming pool became a symbol of the shift. For years, rangers had gathered there in the evenings—sharing stories, watching the sun dip behind the baobabs, sometimes competing for space with paying guests. It had been their place; their norm.

Now, the pool area was reserved for guests. A laminated sign read: “For Registered Guests Only.” The rangers noticed it. They felt it.

One evening, Adiza approached the pool with two junior rangers. They sat quietly on the edge, boots off, feet dangling above the dry tiles. A newly appointed front desk officer walked over.

“Sorry,” she said gently. “This area is reserved.”

Adiza nodded, but her eyes didn’t move. “We used to care for this place. Now we’re told we don’t belong.”

The officer hesitated. “It’s a new policy now.”

The tension grew. Park management tried to mediate, but the lines had already been drawn. The rangers felt displaced—not just from rooms and systems, but from memory. From belonging.

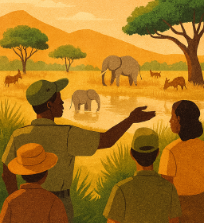

Sensing the strain, Mr. Aanani requested a tour of the national park. “We need to see the land as you see it,” he told the Park Manager. Yawa-Attah agreed. She believed reconciliation could not begin in offices or over memos—it had to begin on the ground.

The next morning, they set out with two park managers and a small group of rangers. The air was cool, the savannah alive with movement. Antelopes darted through the grass, baboons rustled in the acacia trees, and a herd of elephants moved slowly toward a waterhole.

As they walked, the rangers spoke—not about policies or contracts, but about memories. Musah pointed to a clearing where tourists once gathered for sunrise walks. Adiza recalled guiding schoolchildren who had never seen an elephant before. Their voices carried both pride and loss.

Aanani listened carefully. He understood now that the lodge was not just infrastructure—it was woven into the identity of those who had tended it. Yawa-Attah felt the weight of their words. She saw how the new systems, though necessary, had cut into something deeper: belonging.

At the waterhole, the group paused. The elephants drank quietly, their reflections shimmering in the morning light. Yawa-Attah turned to the Park Manager. “We want to build a system that honors this place,” she said. “But we cannot do it without you—and without them.”

The Park Manager nodded. “The lodge is part of the park. The rangers are part of the lodge. If they are locked out, the park itself feels locked out.”

It was not a resolution. But it was a beginning.

That evening, Yawa-Attah wrote in her journal:

“We are not just replacing systems. We are rewriting access. And access is memory.”

And she knew that the second key wasn’t just operational. It was emotional.

Disclaimer

This story is a work of fiction inspired by the operational experiences and sectoral engagements of Hospitality Associates and its collaborators. While the narrative draws upon real industry contexts, any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or real-life events is purely coincidental. Characters, locations, and scenarios have been fictionalized or amalgamated to serve educational and storytelling purposes. The intent is not to critique individuals or institutions, but to distill operational insight through dramatic narrative.